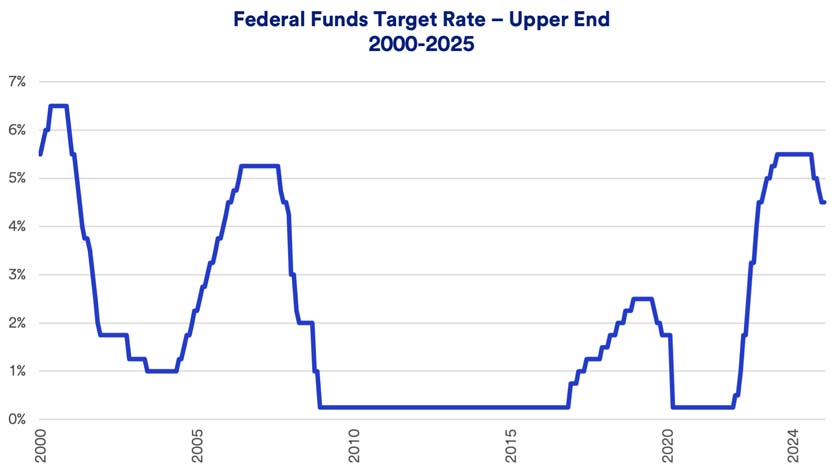

At its previous meeting in December, FOMC members laid the groundwork for reduced rate cut expectations. At that time, they trimmed its projected 2025 rate cuts from four to two. It’s important to keep in mind that expectations can change based on economic developments.

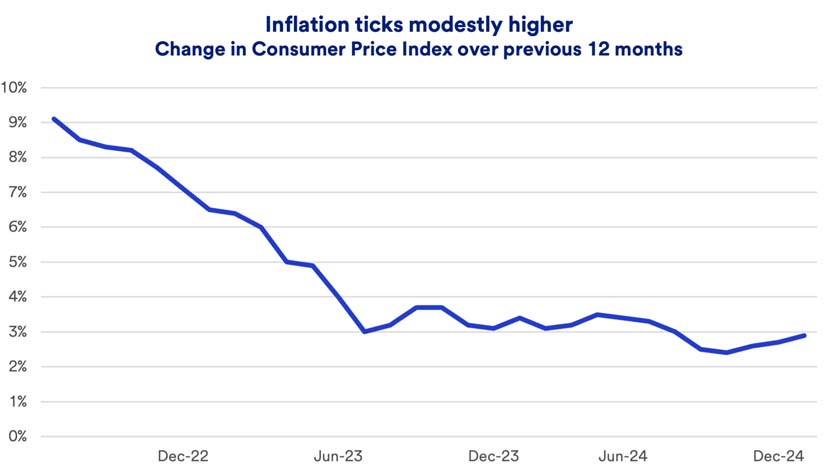

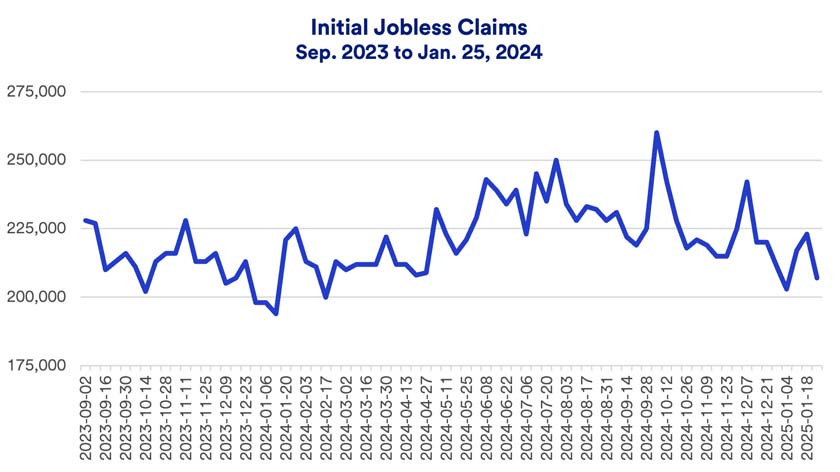

In a statement after the January meeting, the Fed noted that risks to its full employment and low inflation goals are “roughly in balance.” The statement went on to say that the economic outlook is uncertain, and the Committee is attentive to risks on both sides of its dual mandate. The Fed also justified its position of not making another rate cut at this time by stating, “Economic activity has continued to expand at a solid pace (Gross Domestic Product grew at a 3% rate in mid-2024).1 The unemployment rate has stabilized at a low level in recent months (4.1% in December 2024),2 and labor market conditions remain solid. Inflation remains somewhat elevated (2.9% in December 2024)2.”3 Citing current economic conditions, Fed chair Jerome Powell added, “We do not need to be in a hurry to adjust our policy stance.”4

Powell indicated general optimism about the economy’s direction, stating, “We see things as (being) in a really good place for (Fed) policy and for the economy.”4 At the same time, he made clear that while there are encouraging signs, the Fed is still looking for further inflation progress.

“The Fed doesn’t want to see negative implications from its interest rate stance,” says Rob Haworth, senior investment strategist for U.S. Bank Asset Management. “They are likely to remain cautious about further interest rate cuts until they are convinced that inflation for this cycle is subdued.”

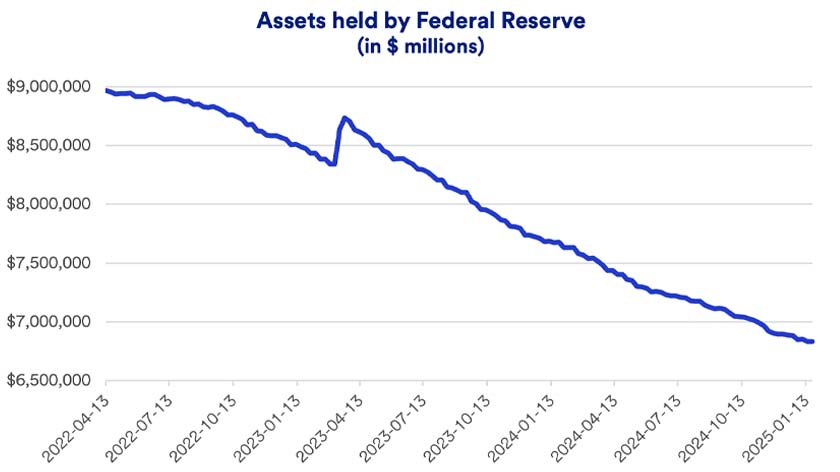

Tracking the Fed’s balance sheet

Along with interest rate actions, another Fed monetary policy tool is its balance sheet of financial assets. During recent challenging economic periods, the Fed tried to boost economic activity by purchasing fixed income assets, such as U.S. government bonds and mortgage-backed securities. The Fed’s market participation helped moderate interest rates. The balance sheet of assets grew to just under $9 trillion in 2022. Since that time, the Fed has reduced its balance sheet, now down to less than $7 trillion.5 In its January statement, the Fed indicated it continues to reduce its bond holdings.3